creating nature-inclusive cities

Have you ever noticed some boxes installed on the building façades? Have you ever guessed what they’re for?

Walking around the cities where we live, we may occasionally notice boxes of different shapes and colours fixed to building façades at various heights.

People often assume these are electrical boxes, but there is a more specific explanation: they are nesting boxes for birds and bats, designed to encourage their presence in areas where trees are scarce and difficult for our flying friends to access. These strategies aim to enhance biodiversity within our busy and polluted built environments, meeting green policy requirements.

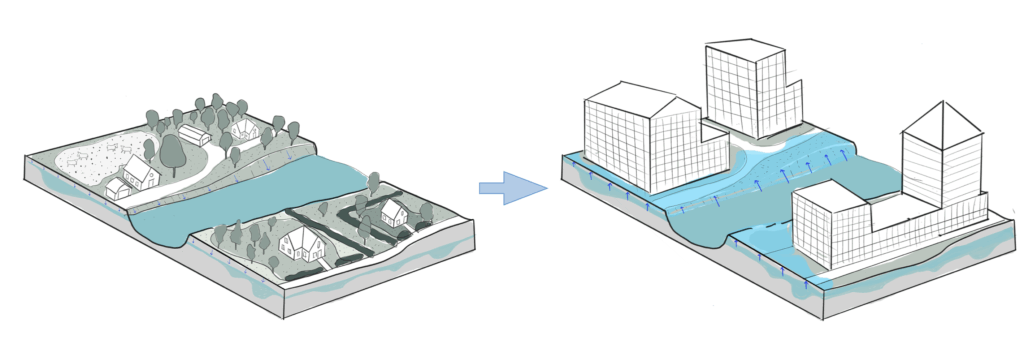

As part of a macro-ecosystem, humans are tasked with the mission to protect biodiversity and the natural environment. In this era of rapid development and housing shortages in large cities, we have begun to build faster and more frequently. Human developments are quickly taking over land and forests, covering waterways, and constructing too close to riverbanks and shorelines. These are the places where nature hosts birds, animals, insects, and plants of all species—and which naturally perform functions necessary for the maintenance of our shared environment.

In this article, we address the causes of changes in the natural environment, and we explore how these can be mitigated. What are the principles of contemporary design processes that aim to protect the environment and ensure our safety? Have our countries and cities implemented strategies to address climate challenges?

Our impact as humans is affecting biodiversity that has existed and thrived on this planet long before we began to populate it. Tackling these environmental issues has now become a global mission, and it is worth considering what policies and strategies institutions have adopted.

Where It All Began

Environmental awareness in urban design really took off in the 1990s, when researchers and policymakers started to address the ecological impacts of rapid urbanization. One of the first big steps came from Northern Europe, where Berlin introduced the Biotope Area Factor (BAF) in 1994. It was a new way of making sure that green spaces remained part of city planning — even in dense urban areas.

The idea quickly spread across Europe, America, Australia, and Asia, and has since evolved into what we now call the Urban Greening Factor (UGF).

The Urban Greening Factor

Today, the Urban Greening Factor (UGF) is a planning tool adopted by the European Union to increase the presence of green infrastructure and its benefits in addressing climate issues. It is used to ensure that green infrastructure forms a fundamental part of site design. It’s basically a scoring system that helps designers, planners, and developers measure how much green infrastructure (trees, gardens, green roofs, and water features) is included in a project. While it remains voluntary in some areas, it is now a requirement in cities such as London and Amsterdam.

The UGF ensures that future urban developments include landscaping of sufficient quantity and quality to contribute to a broader vision of green infrastructure (GI)—a “network of green spaces” that is planned, designed, and managed to deliver a range of benefits including healthier urban living, flood mitigation, improved air and water quality, urban cooling, and enhanced biodiversity and ecological resilience.

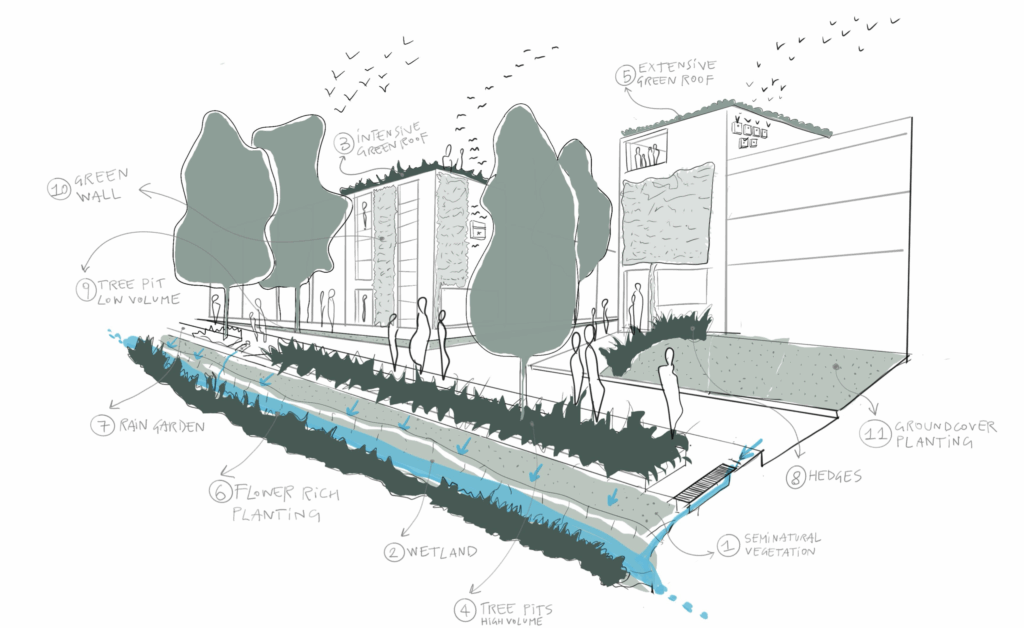

The indicator is calculated using information provided in the Urban Greening Factor Guidelines, designed for use by landscape architects, ecologists, and planners. Different types of urban greening in built developments are grouped by type and measured per m², m³, or linear meter to indicate their relative value as nature-based solutions. These are analyzed according to factors such as:

- Semi-natural vegetation (m²)

- Wetland or open water

- Intensive green roof (m²)

- Tree pits (high-volume soil)

- Extensive green roof (m² and depth)

- Flower-rich perennial planting (m²)

- Rain gardens / other SUDs (m² and depth)

- Hedges (linear meters)

- Tree pits (low-volume soil) (m³)

- Green walls (m²)

- Groundcover planting (m²)

How the Urban greening factor Works

The criteria are combined in a table, which gives the value required for planning approval. Integrating features such as permeable paving, rain gardens, swales, wadis, green roofs, tree planting, and flower meadows that attract fauna and improve flora increases the chances of project approval.

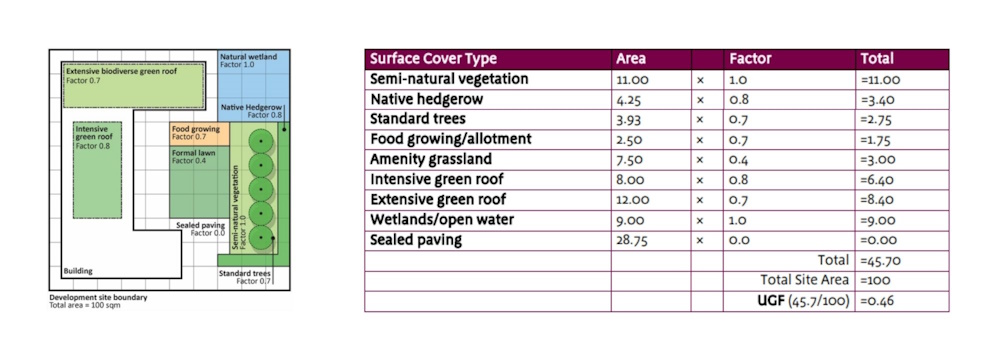

The plan and table below illustrate how the UGF works, showing the final score generated by each category.

Each element is given a score, which indicates its natural-ness and functionality. In the UK, the factors range from 1.0 for semi-natural vegetation, 0.8 for green roofs, 0.4 for mown amenity grass, and 0 for impermeable sealed surfaces.

In the Netherlands, they have developed its own calculation method, “Puntensysteem voor Natuurinclusief Bouwen” (Points System for Nature-Inclusive Building), which, also provides guidance on the use of indigenous plant species.

why we use the urban greening factor

Both the UK and Dutch policies are designed to quantify and encourage greener and more biodiverse urban development, though they differ in origin, structure, focus, and application. The UK’s UGF is primarily a planning tool to ensure sufficient green coverage in urban areas, while the Dutch PNVN is a biodiversity integration tool that rewards qualitative ecological improvements in buildings and landscapes.

As designers and inhabitants of the natural environment, we should all be aware of the importance of these guidelines in our built environment and how they can positively impact our lives.

The UGF is an example of how we can address the issues caused by human activity on this planet and envision a greener, healthier future for the next generations. By following scientific, we can help foster an environmentally conscious mindset in future generations, encouraging greater sensitivity to ecological issues—especially those threatening the natural systems we inhabit and our own existence as “guests” on this extraordinary planet.

Conclusion

As our cities continue to grow and densify, the challenge of balancing human progress with ecological integrity becomes ever more urgent. Tools like the Urban Greening Factor and the Dutch Points System for Nature-Inclusive Building remind us that the built environment is not separate from nature, but part of it.

Every green roof, nesting box, rain garden, or native planting scheme contributes to a living network that brings balance back to our ecosystems. These interventions are small in scale but huge in impact; they support the species with whom we share our cities, improve our collective well-being, and help cities adapt to a changing climate.

Ultimately, the success of these strategies depends on a shift in mindset: from seeing nature as a backdrop to recognizing it as a collaborator in design. By embedding ecological thinking into every phase of the design process, we can ensure that our cities remain resilient, regenerative, and alive for every living creature that calls them home.