09 Apr Landscape restoration: An Interview with John Hart Asher

Interview with John Hart Asher from Blackland Collaborative

by Eirini Trachana

At MOSS, we design with nature in focus. To further enrich our designs with ecological principles, we engaged in an insightful interview with John Hart Asher, senior environmental designer and principal at Blackland Collaborative. Our objective was to gain a profound understanding of ecology and landscape restoration, enhancing our approach to design.

“A woodsman looks out on a square mile of prairie and sees only grass. But a prairie person looks at a square foot and sees a universe!”

Introduction

A landscape can get out of balance due to intensive land use. What can we do in this case? In this post, we learn from an expert, John Hart Asher, “People see green, and they say ‘Oh look out there, it’s all green, it’s nature, it’s wonderful.’ That’s not the case. ‘A woodsman looks out on a square mile of prairie and sees only grass. But a prairie person looks at a square foot and sees a universe!’ That’s what Bill Holm, an American poet, essayist, and musician, says, and that’s what we are trying to reach, to read the landscape and apply the necessary tools to reclaim its diversity in every scale.”

In the following chapters, we will examine:

- The Need for Landscape Restoration

- The Steps for a Landscape Restoration

- The Best Project Scale for Landscape Restoration

- A Surprising Aspect: The Role of Education

Despite starting with a Master’s in underwater archaeology, John Hart’s passion for nature and plants led him to pursue a Master’s in landscape architecture at the University of Texas. He told us, “In my background, I have vivid memories of going to the food garden with my grandmother, picking okra and tomatoes. I was inspired by seeing how useful plants are, and how important they are for wildlife, and noticing the joy plants bring.” During his studies, he came in touch with The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, and then “everything came together in a place where I could do something that affects not just people, but can benefit natural processes and species, and ultimately profit people as well. Then, I zoomed in on that approach with native plants and got into the Wildflower Center program working on Ecological Restoration.”

“Landscape restoration is not only about aesthetics.”

The Need for Landscape Restoration

Looking at Blackland Collaborative’s website, their mission is to create diverse ecosystems that reconnect people and nature. At MOSS, our commitment aligns with this mission, and we specialize in crafting site-specific designs that delve deep into the ecology of each region. We aim to design not only for humans but also to attract and take care of the biodiversity in the project site, like plants, small avian species, and beneficial insects. We admire John Hart for his approach to landscape restoration, prompting us to arrange an interview with him. “People would ask to restore their land to a ‘historic climax condition,’ as in, what it was at its most biodiverse state. The city says we want more green, we want to be more sustainable, we want to address heat island mitigation, we want to talk about biodiversity, we want to talk about air quality, water quality.” These topics emerge from recent research on climate change, endangered species, and landscape sustainability. A viable path towards achieving a more sustainable landscape involves restoring it to its natural state.

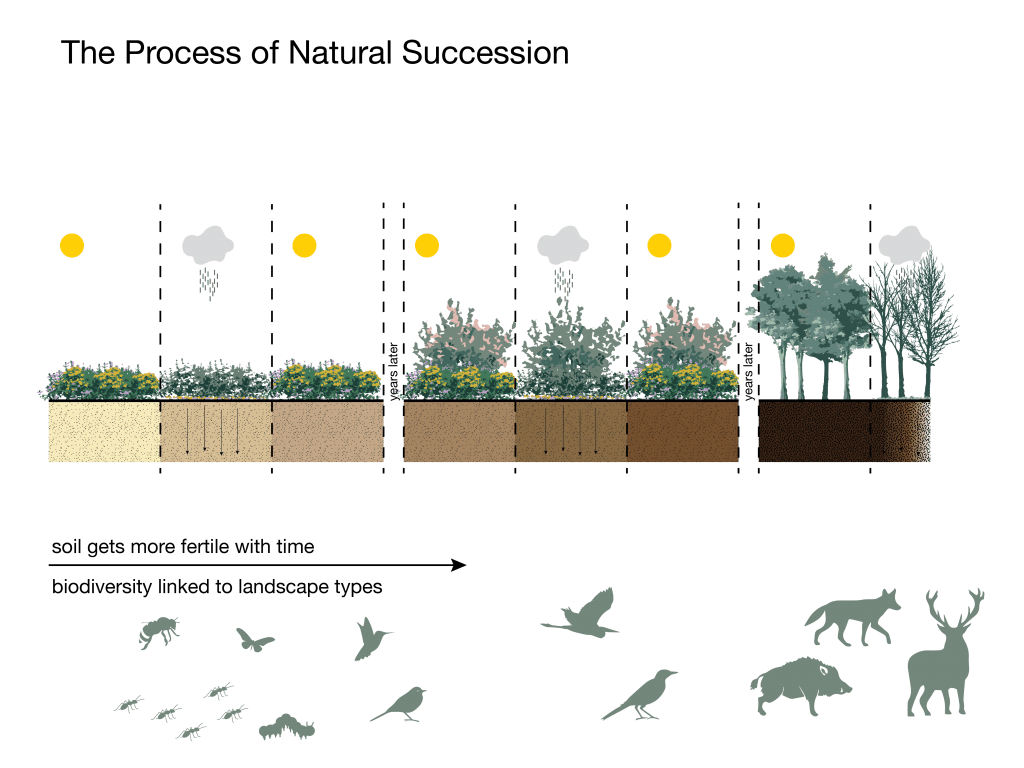

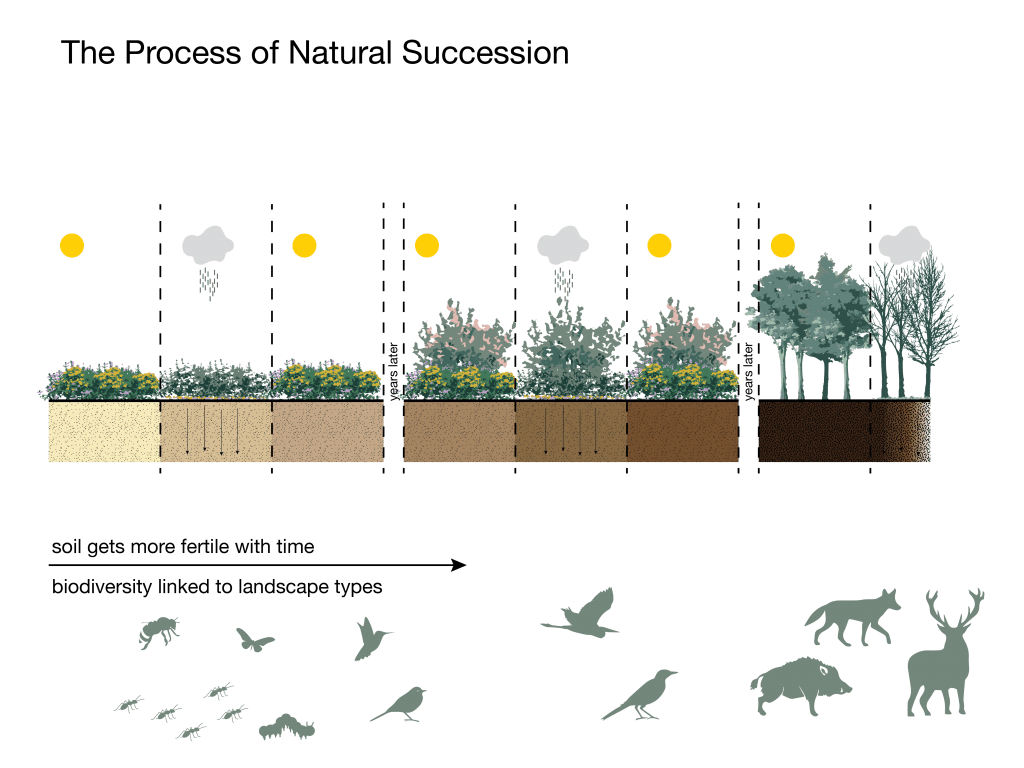

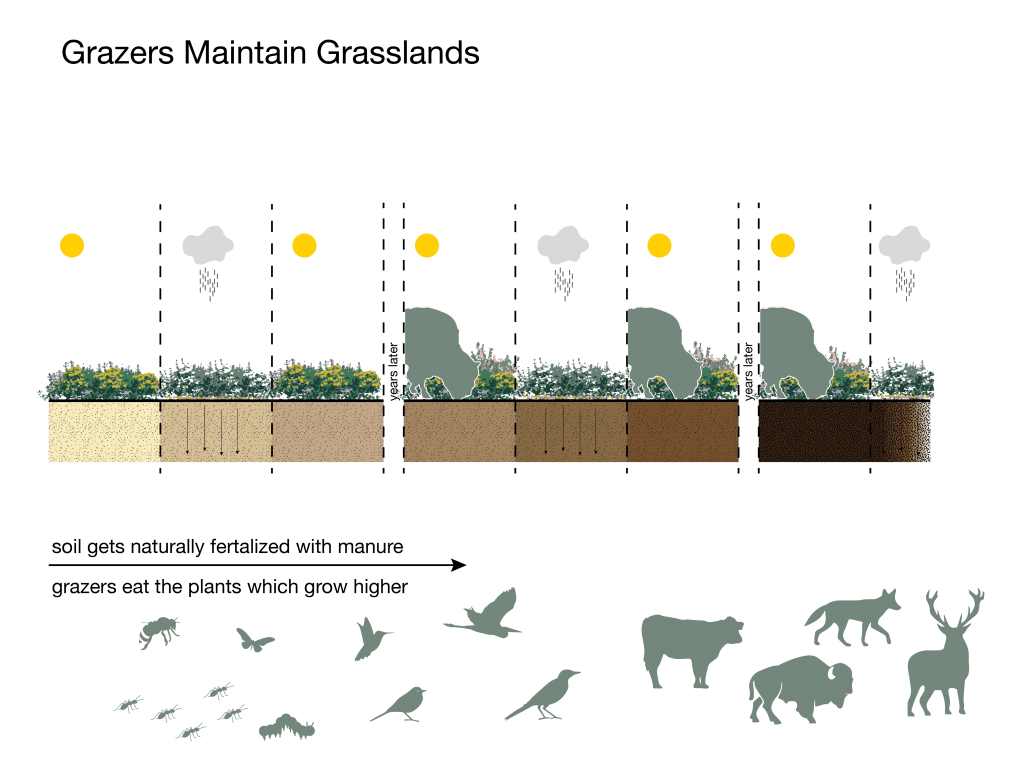

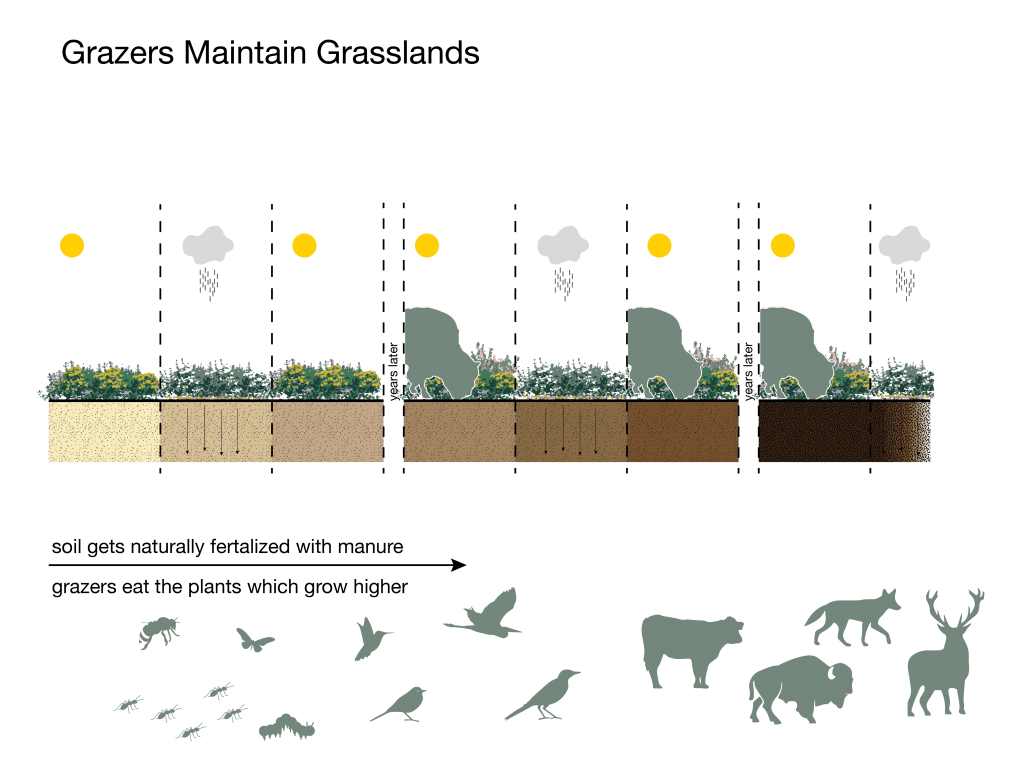

Landscape restoration is site-specific. We understand this better with John Hart’s explanation, “In the United States, grasslands were a large biome. Our land has big prairies where birds and other species can see predators coming. Grasslands are important; local species can live there and feel secure. Animals that depend on these environments must be given equal priority with people. Without wildfires and grazers, grasslands can transform into woodlands, altering entire ecosystems.”

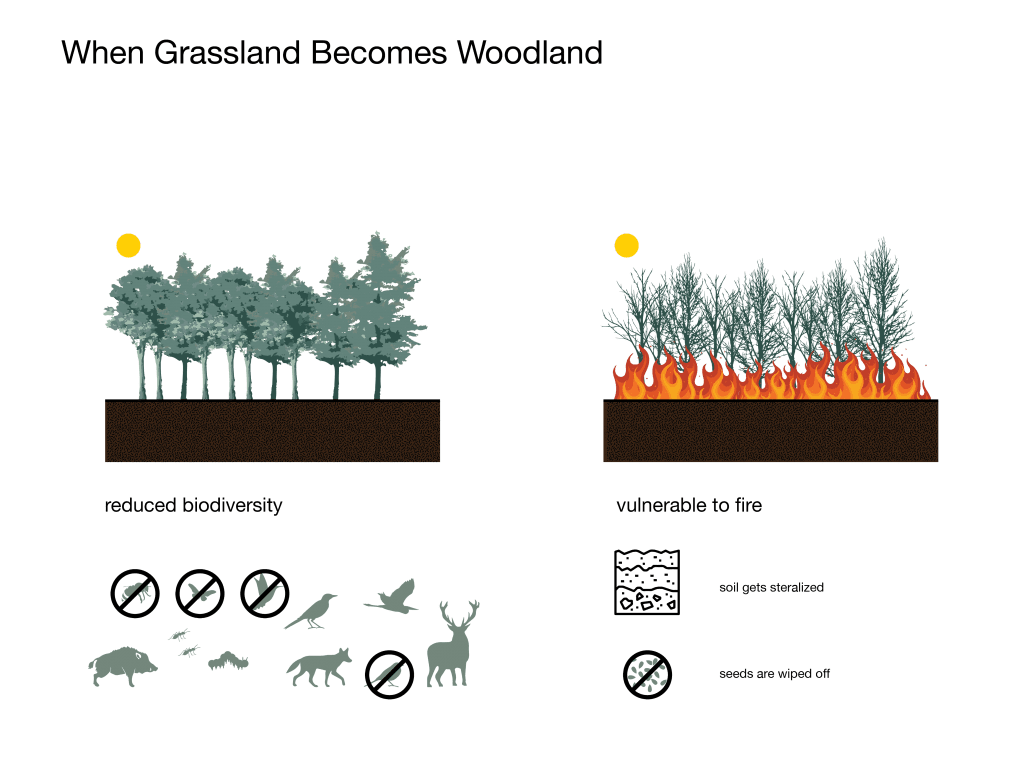

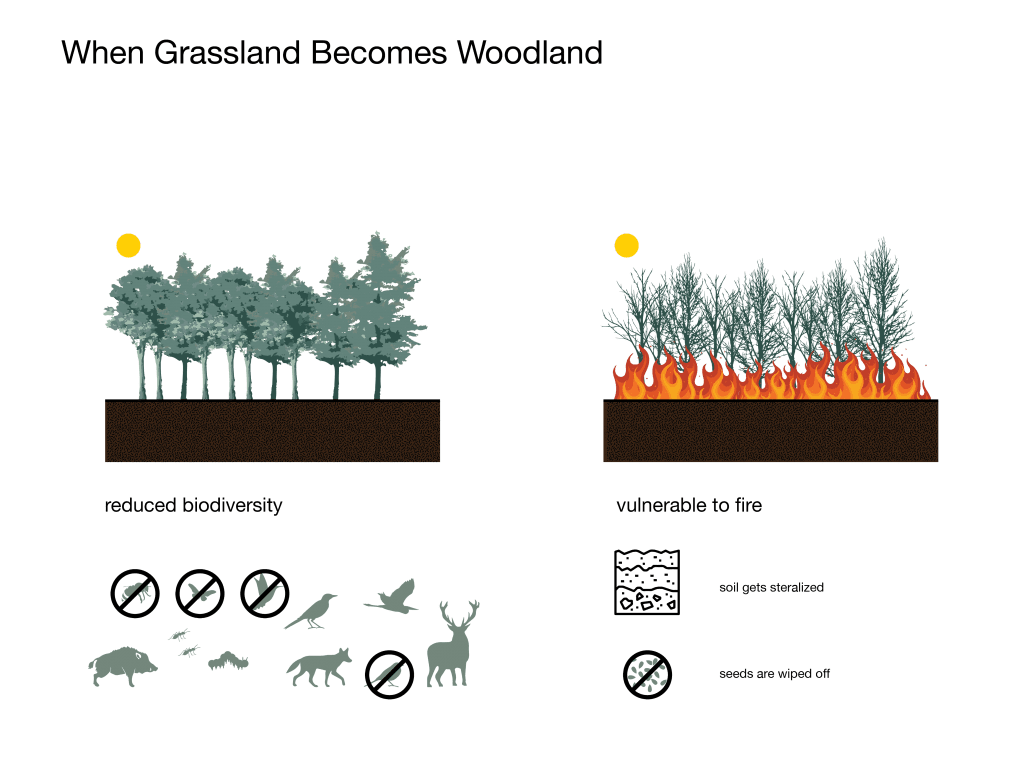

When woodlands replace grasslands, they have two significant adverse effects on the landscape. Firstly, the biodiversity within woodlands diminishes as sun-loving prairie plants, grassland birds, and various animal species find it increasingly challenging to thrive. Secondly, these “new” woodlands do not represent historical plant communities and are more vulnerable to drought-induced wildfires, which can have catastrophic consequences. These woodlands are now located in regions that experience regular fire, usually every ten to eleven years. “Landscape restoration is not only about aesthetics. The absence of regular wildfires, or prescribed fires, has led to catastrophic wildfires, as trees replace grasslands over decades, if not a century, creating highly flammable ‘fuel.’ This cycle harms the landscape by sterilizing soils and destroying seeds. Implementing regular, prescribed fires every three to five years removes this fuel buildup, mitigating the risk of catastrophic fires.”

The Steps for a Landscape Restoration

Following the analysis of the significance of landscape restoration, discussions ensued regarding methods to accomplish it. Restoration starts with assessing the site, monitoring plant species, analyzing invasive and successional plants, creating a restoration plan, working closely with the installation team, and monitoring the project’s development as it progresses.

John Hart thinks that getting the process started correctly is crucial. “Before initiating any project, we thoroughly assess the site to understand its current condition, including soil composition and species present. That leads to a landscape management plan or restoration plan. Proper preparation is crucial for project success.”

Once the team prepares the site, the subsequent step is the installation of the project. “Along with collaborating closely with the construction team, we will redline and review drawings. A key service that we provide is post-installation monitoring. We go to the project site, record the process, and write reviews about the issues that might come up. Landscape restoration and the development of every project in the future are complex because nature is complex.”

In summary, the most crucial components of the landscape restoration process are site preparation, effective installation, and future project development monitoring.

The Best Project Scale for Landscape Restoration

The question that came up next is, what is the scale of those projects? Does this work apply only to large-scale grasslands? Is it applicable to small-scale projects? “We work on multiple scales,” said John Hart, “a lot of our projects are large scale because the teams we cooperate with on those projects need the help.

We are still happy to work with private landowners, as well. If everybody takes up a third of their land and adds a native plant community, we can see a massive impact on biodiversity and climate change. That starts to change the game!

We have projects where a homeowner wants a pocket prairie in their backyard. We have two options: to either design and carry out the project on their behalf or to educate people on ‘How to design and create a pocket prairie.’ We offer classes to teach them how to consider the climate conditions, check the soil, and the kind of plant mixes they can use. Some of these talks are free. We are mission-driven. We want to help save the world!”

This response brings us to the final chapter of this blog, which focuses on the role of education. It’s inspiring to learn that Blackland Collaborative actively educates people about the individual actions that can contribute to healthier landscapes. At MOSS, we are also eager to share the knowledge and passion for green spaces through workshops, masterclasses, and tours. We’re committed to showcasing the benefits of green spaces for our well-being, productivity, and mental health. Through our MOSS Lab research, we collaborate with Wageningen University to explore how plants impact our lives, and we share our results online and in seminars. Is there something about the natural environment or biophilic design that you are curious about? Reach out to us to collaborate!

“If everybody takes up a third of their land and adds a native plant community, we can see a massive impact on biodiversity and climate change. That starts to change the game!“

A Surprising Aspect: The Role of Education

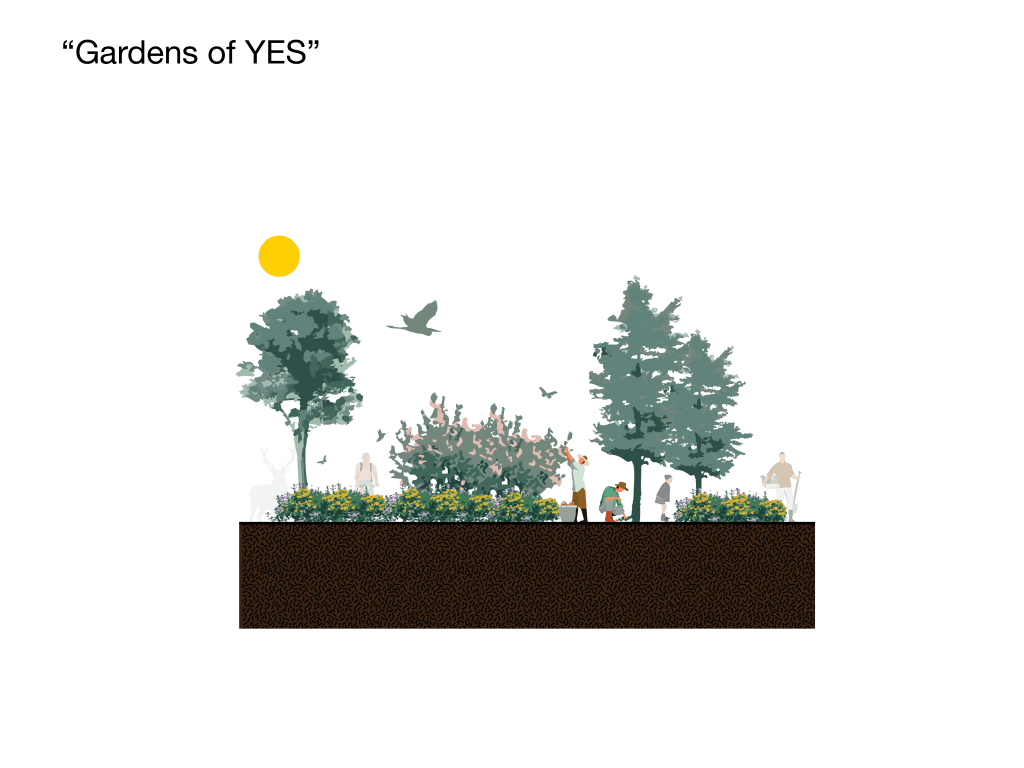

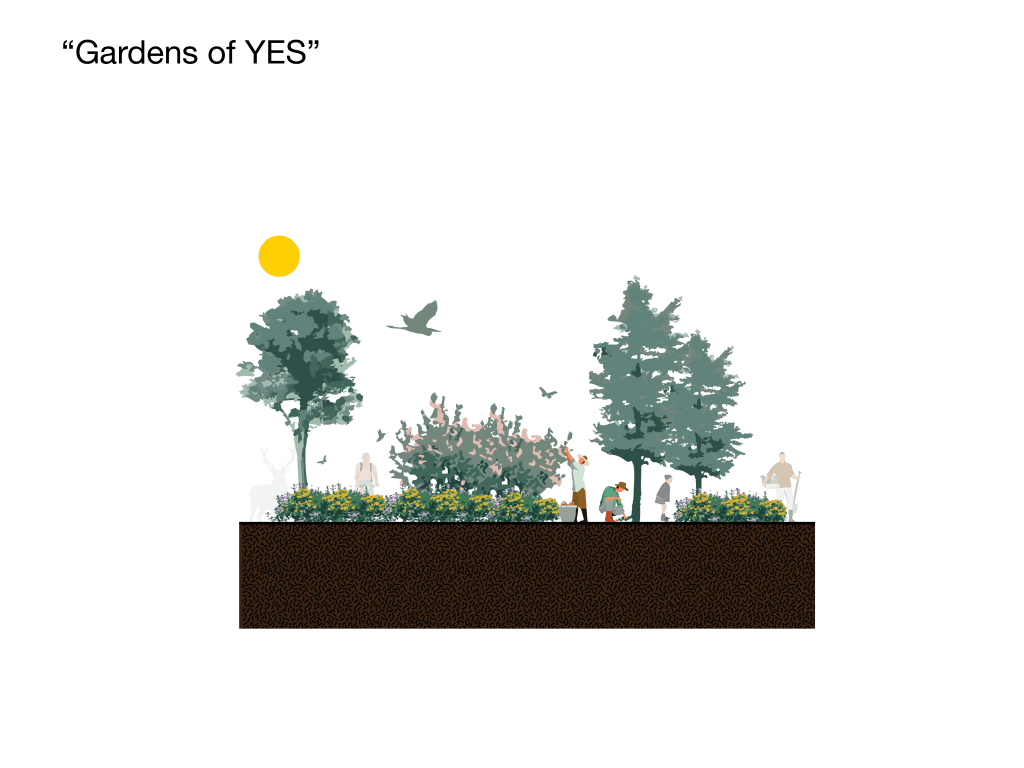

The most intriguing aspect of this conversation with John Hart lies in how experts can educate people about the fundamentals of preserving nature while also fostering a shift in perspective regarding the utilization of our gardens, parks, or designed landscapes. “Currently, we add labels to the gardens: ‘Don’t step on the grass, don’t pick the flowers.’ We want the gardens we create to be ‘gardens of yes.’ Touch the plants and explore! We want that interaction. People only conserve what they know and love.”

The move in landscape architecture towards “wild gardens” promotes natural growth and awareness of its benefits. How can we boost biodiversity in landscapes, why is it vital, and what are the gains?“We focus on training individuals to recognize successional species and identify invasive ones. People see this work as a threat because they perceive fires as dangerous and catastrophic. We need to work on people’s culture of fear through education.”

John Hart’s perspective on reconnecting people with the landscape, educating them to understand its components, and teaching them ways to preserve it offers valuable food for thought. He says, “That connection is important because for so long it’s been ‘Oh, if we truly want to conserve this land, we need to put nature here, people over there,’ and that’s what’s gotten us in this mess in the first place. We are nature; we’re part of that!”

Conclusion

“I can look at myself in the mirror with the work I’m doing and say I am part of the solution. I feel that we do have an obligation to repair our damaged landscapes.”

Despite the recent shift in landscape architecture away from trying to get total control over nature, John Hart suggests educating people, the primary users of the landscape, so they can forge a deeper connection with it, understand its nuances, and re-establish their bond with it. The role of experts extends beyond analyzing, researching, and managing landscape restoration processes; it also involves restoring the lost connection between users and the landscape. Let’s create “gardens of yes”!