20 Feb Building ecology: an interview with Ronald Buiting

by Caterina Fagiolari

As a company that works in sustainability we often wonder: how can we design spaces that are not only aesthetically pleasing, but that can also support the natural world around us? We had a talk with the ecologist Ronald Buiting to better understand the relationship between landscape design and ecology.

We talked with him about three main topics related to landscape design and ecology: the forest, the city and the design itself. Firstly, let’s learn more about Ronald Buiting: he began his career in ecology when, in the Seventies, he met a representative of the IVN group Vecht en Plassengebied, an association that today consist of two hundred members, including a large number of experts. On that day the association, one of the first in the Netherlands, was pruning the willows, the wood of which is used to light fires in the fireplace, for gardens and for various household activities in the Netherlands.

He told us “I met a guy there, and he’s been my hero. He said to me: ‘are you interested in working in landscape?’ And I was 13 years old so I thought ‘why not?’ […] That changed my life, because from that moment I knew that I wanted to do something with nature. I knew I wanted to do something with forestry.”

Subsequently, Ronald Buiting devoted himself to the study of forestry on a practical level, specialising in taking Italian Poplar away, planting it in Holland, so that everyone could learn about it. He then mastered in forestry in university, which he interrupted shortly before finishing his PhD in philosophy, to open his own business: Buiting Advies, an ecology consultancy company that works in both rural and urban areas.

Their range of services today varies from practical work such as blading and making inventories of plants, to planning, researching and advicing. But, at the beginning, his activity with Buiting Advies was blessing the trees: “We had to paint the trunk to mark the trees, we did it with a small piece of equipment. With these tools you can color the bark on two sides, and that’s a bless. It’s a strange word, because it’s not a blessing as the tree will be killed.” From that moment Buiting Advies started to grow, moving more towards ecology.

THE FOREST

A perfect example of their work today, and also Ronald’s favorite, is Noorderbos, a 108ha intensively used forest park, located north of Tilburg and realized on the former municipal fluid fields. During construction (1999 – 2001), the ‘wild-heterogeneous planting‘ developed by Buiting Advies was applied here for the first time. Now, 22 years later, it is easy to see how a wild-heterogeneously planted forest develops: there is a lot of diversity in height, thickness, crown shapes, stem number and openness.

While commenting on the design methodology Ronald Buiting explains that “for a long time we thought that in a natural forest there was an individual mix of old trees and young trees. We thought that there were trees that are 800 years old and trees that are five years old in between them, and so on. And then in the Seventies a new research started. I found out that this theory wasn’t exact, there was more. The forest is a big puzzle with old pieces and young pieces. They have different sizes, different densities and different structures. And sometimes, you have one puzzle piece, but then a big tree falls on it. A new phenomenon starts in this old puzzle piece, but this doesn’t change the age of that specific part.”

The ‘wild-heterogeneous planting system’ is currently applied in many locations in the Netherlands and has proven to produce beautiful and varied forests with high natural value. And that happens in, forest terms, a “short time”.

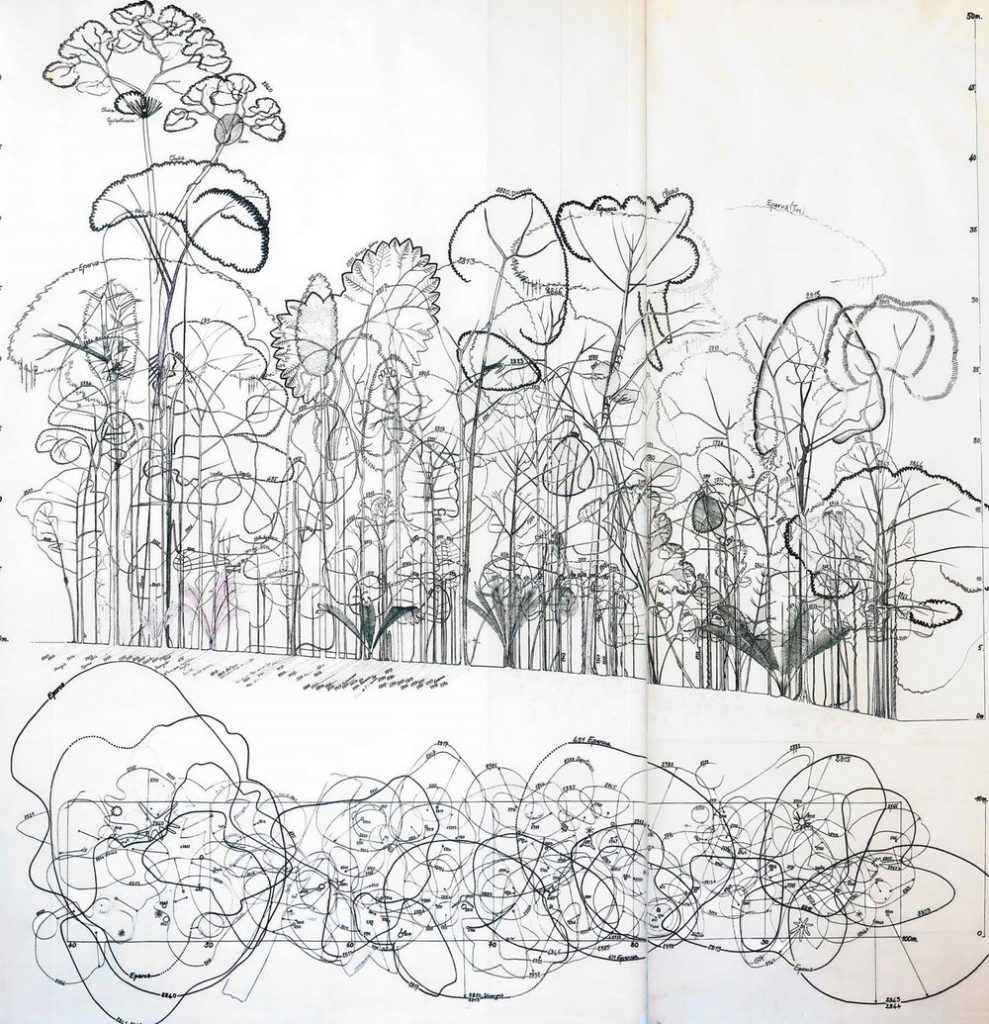

This school of thought, he explains, is mainly based on the theories of two professors: Roelof A. Oldeman and Francis Hallé. “I studied in university with a very special professor, Professor Oldeman. He was, as we say, phenomenologically looking at things. If you follow his method you’re not going to measure, you are only going to look, make drawings, try things and look if and how they work.”

“I knew them well.” continues Ronald talking about Oldeman and Hallé “And I’m maybe the only one of that school that is practicing their theories, making things from what they said in university to the practice. Noorderbos is the most important example on earth because it’s the first one. If you looked at it from above you would see the same thing you see in a virgin forest: a cauliflower structure.

Most forests in the Netherlands, however, have been planted not more than 20 years ago. In the 70s and 80s, there was no forest at all. […] And then we started planting, of course, plantations. But if you look at what society asks at the moment from the forest, it is not the wood that is important. We have enough wood on a European scale. In a small country like the Netherlands it is important that we have biodiversity, beauty, places to run, places to sit, places to have a picnic and so on. And that means that the forest must be transformed from a plantation into an ecosystem.”

Why do you think we are so attached to plantations?

“The main reason is that we are still agricultural thinking. And agricultural thinking means that the system must be cheap, fast and easy. It has some roots in our culture. And so we think in that way, even if we don’t want to.”

THE CITY

What changes when we talk about nature in an urban context, like a city? How is it different to do ecological consulting in urban projects?

When we talked about the forest we gave extreme importance to the overlapping layers of nature, to the spontaneous progression of events, but when we talk about the city we don’t just design for animals and the ecosystem, we also design for humans.

He specifies: “In a building environment, you can only make habitat for what we call generalists.” A generalist is a species that has a broad niche and is able to adapt in many environmental conditions.

They do not have a limited diet and are able to survive by using a variety of resources. We can’t introduce specific species in the city as they can’t live in a built environment. They need specific plants, nectar, and conditions. But still we can help the ecosystem and biodiversity. The city environment is more suitable for the generalists, that are still very important for the bigger ecosystem.

Ronald Buiting gives the example of the Alcon Blue Butterfly. Like some other species, the larval stage of this insect depends on support by certain ants. The larvae emit surface chemicals that closely match those of ant larvae, causing the ants to carry them into their nests and place them in their brood chambers. In order for this to happen the presence of the Gentian flower is needed, but also the correct environmental conditions that allow the butterfly to be ‘adopted’ by the ants without interference with other insects that can change the smell of the larvae.

“It is an extremely rare process.” Explains Ronald “It’s difficult even when it happens in nature. That’s not possible to make it happen in the city.”

Then, for whom do we design natural spaces in urban environments? For people or for animals?

“When we design in a city environment, a built environment, we do nature for the people. We attract big butterflies, if possible, because then people see them, and it makes them happy. And it’s nice if there are rare species coming, but it’s not the thing we focus on.

But, attracting species is also important for the people, because we want biodiversity not to get any lower than it is already, even if people will recognize just some insects.

There is a project, for example, that we have done in the dunes and it is for the Narrow Mouthed Whorl Snail.” The dunes are a habitat with some protected species, and working on that means working on preserving the ecosystem. Buiting Advies had, for this reason, to work on preserving the Narrow Mouthed Whorl Snail, even if “Nobody will ever see it, it’s 2 mm long. But, if the environment is good for the Narrow Mouthed Whorl Snail, all the other species will be happy in the same conditions. Even if what we attract in a city environment is more for humans, we’ve been educated that biodiversity is super important, because otherwise everything, the entire ecosystem will collapse.

We still try to attract some specific insects, but it’s not the main thing. The main thing is, in a city, to create nature that is visible for the people that live there.”

What are the key elements for the maintenance and development of an ecosystem that are applicable to the city?

“Nectar, all year.

We plant grasses, small flowers, shrubs and trees that give nectar after each other, like a chain link into the Nectar calendar. The Nectar calendar has to be fulfilled so that in every month of the year, insects will have access to nectar.”

But also ‘Housing’. For bees, for bats, for birds. The best thing is when you don’t see them, if they are hidden. Of course,” he proceeds on this subject “the animal to which we must pay most attention is the bee. But my idea is not to think about taking care of only a special insect.

We did it once, we helped with the design for the Slachthuissiteugs house in Antwerpen. I had a student that specialized in bees. And I asked him, as we always ask, ‘could you tell me what kind of species there are around?’ And, I think it took him three minutes, he said ‘the Red Mason Bee is fundamental’. It’s a very special insect. You never see it, but if the project is done perfectly for the Red Mason Bee, it’s also done perfectly for every other bee.

When the environment is good for bees and butterflies and other insects, it’s okay for birds and it’s okay for bats. Of course, all these animals also got their place in the design, but it all started with the Red Mason Bee.

Normally, I think we can say that it’s not an individual system that we’re looking at. It is an ecosystem and everything is in connection with the rest. If you design something green, healthy, biodiverse and natural, then you attract some species, maybe it’s not the specific butterfly you expected, but something else is coming anyway.”

THE DESIGN

How do these reflections enter into the planning of a city? On a larger scale, how can we accommodate these animals and help people’s well-being?

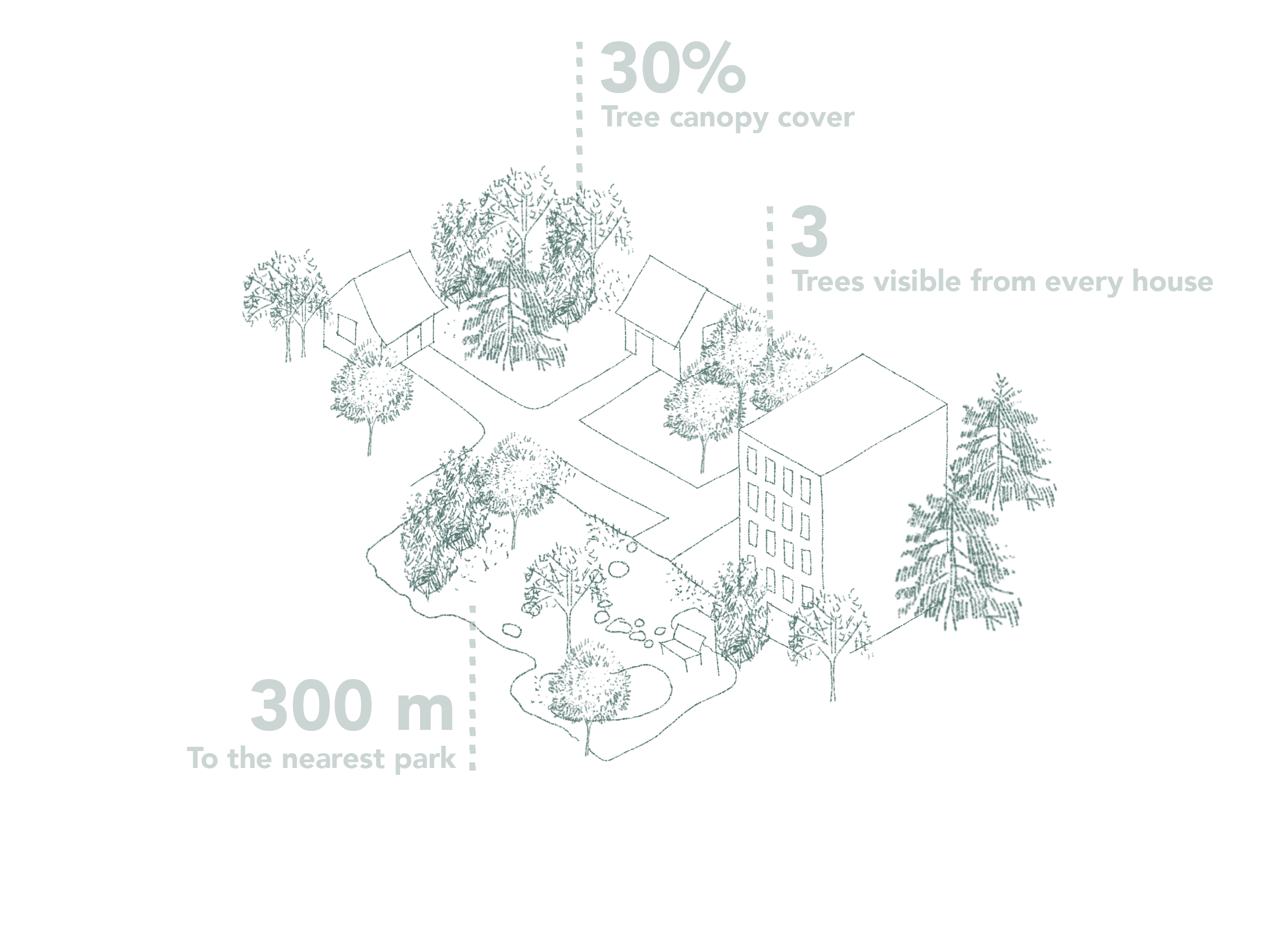

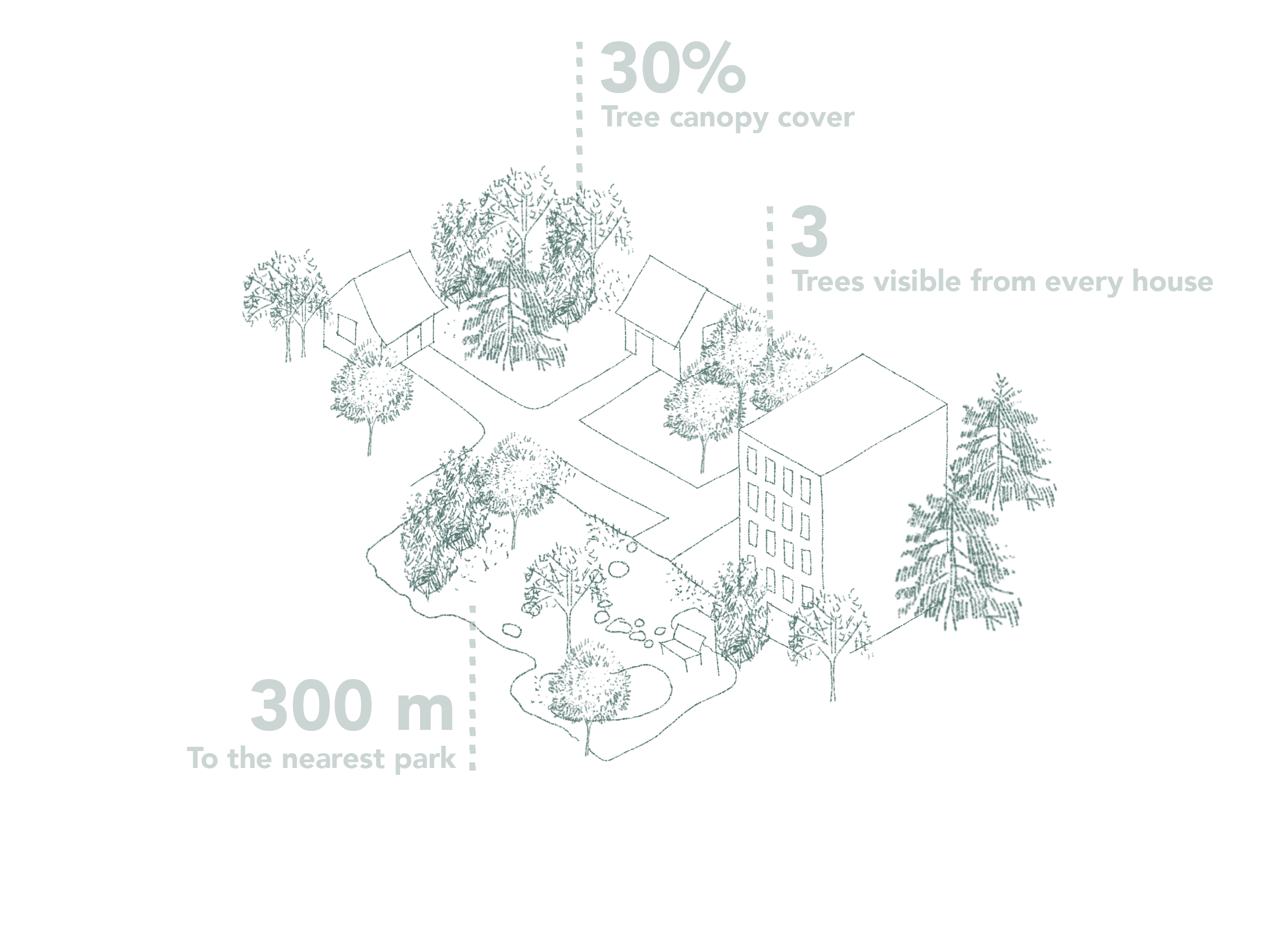

“Do you know 3-30-300 rule?” Asks Ronald Buiting. “It should be, I think, the basis of all designs.” This evidence-based rule proposed by Cecil Konijnendijk focuses on the crucial contributions of urban forests and other urban nature to our health and wellbeing, as well as climate change adaptation.

The rule provides clear criteria for the minimum provision of urban trees in our urban communities:

- 3 trees from every home

- 30 percent tree canopy cover in every neighborhood

- 300 metres from the nearest public park or green space

The first rule sets that every citizen should be able to see at least three trees (of a decent size) from their home, the second one has been deducted from studies that have shown an association between urban forest canopy and, for example, cooling, better microclimates, mental and physical health, and possibly also reducing air pollution and noise.

The third one comes from the fact that many studies have highlighted the importance of proximity and easy access to high-quality green space that can be used for recreation. A safe 5-minute walk or 10-minute stroll is often referred to. The European Regional Office of the World Health Organization recommends a maximum distance of 300 metres to the nearest green space (of at least one hectare). This encourages the recreational use of green space with impacts on both physical and mental health.

“We work together with municipalities, we plant the trees from the corporations. We calculate how big the crowns will be when the trees are grown. Then we see where we miss which percentage and where we should plant new trees. And we believe that leads to plant a million trees. We try to apply this rule step by step. And then, of course we plant trees that give nectar after each other, like a chain link. A link into the Nectar calendar, as previously said.”

CONCLUSION

To sum up, we had a reflection with Ronald on how building with architecture requires a look to the future, and, on the contrary, working with natural life power requires a study of the past.

Everything in nature is happening, has happened and will happen not because it is designed, but because life power is doing his job. Designers work is to just help life power to start the engine giving nature a small push.

“A lot of thinking and a lot of intelligence and a lot of knowledge are needed to do the right thing and to then leave the process to nature.”

Want to learn more about Buiting Advies work? Check out Buiting website or reach out to the MOSS team.