29 Apr The necessity of rewilding our cities

by Sarah Fastnacht

We are a small part of a much bigger system: Nature. It is what makes life possible for us. The energy that sustains us, the water we drink, the food we eat, where our bodies will eventually return to. Every living being is a part of this complex system. As we leave nature out of the equation of our daily lives, there are direct consequences to human health and the integrity of the system as a whole is subject to fail. As Thomas Elmqvist said, we must “…integrate the goals of well functioning cities with that of well functioning ecosystems” (2).

FIRST-OFF, WHAT IS REWILDING?

A word with many definitions. In summary, it is the action of reintroducing spaces for ecosystems to become self-regulating for the mutual benefit of humans and non-humans alike. This requires stepping away from the heavily curated, monoculture parks we know today and venturing on the wild side.

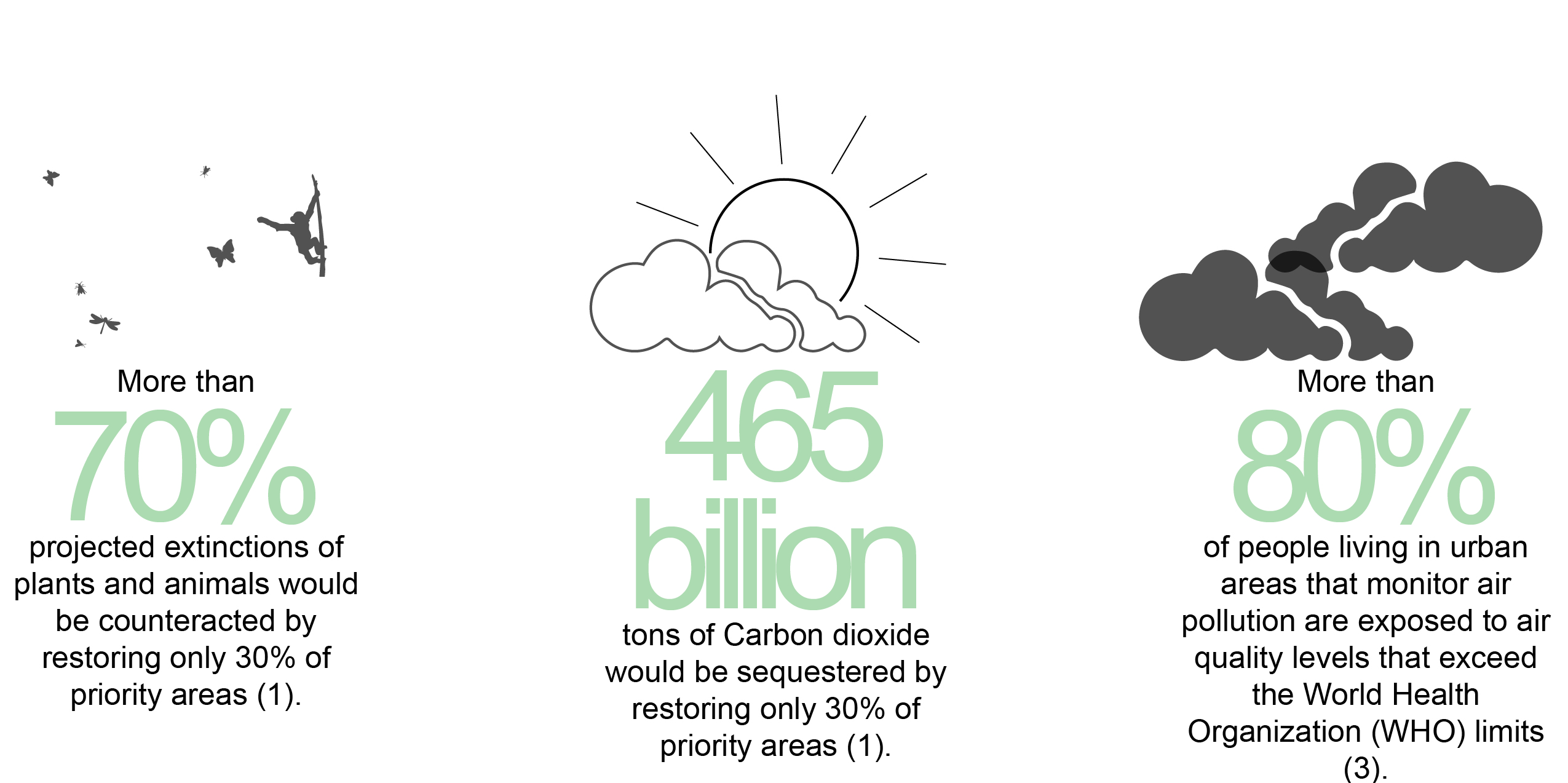

Many big cities are synonymous with air and noise pollution, lack of nature, smog, urban heat island effect. With the upward trend of urbanization, rewilding our cities is essential in thinking about the health of our planet and its inhabitants. Through habitat loss, increase in air pollution, and soil degradation among other negative effects, native ecosystems are disrupted to an extent that is unhealthy for both the planet and everyone living in it.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

Re-naturing and rewilding shouldn’t require completely changing city layouts. Many cities are already experimenting with this theory. By creating a green corridor between parks including green roofs and walls, London was able to bring back multiple species to the city including a rare bird – the black redstart!

Both integrating green infrastructure and keeping as many native species on the land as possible is integral in creating a healthy symbiosis with nature. Barcelona is another example of a city taking steps towards re-naturalizing by bringing 783,300 sq metres of green open space to the city, including 200 nesting towers, insect hotels and beehives.

As climate change forces the world to move towards environmental protection and regeneration measures, design firms will have to shift their mindsets as well. MOSS has had years of working in this field, and has a wealth of knowledge and passion in the power nature has. In Max & Moore, green roofs and walls were integrated to be a home for endangered plant and animal species. In Dura-Vermeer, MOSS was able to bring insect hotels and native plantings into their green roofs. When we design for our ecosystems, the benefits can be seen in every aspect of our lives. Healthier ecosystems = healthier communities.

“We need to recognise ‘urban green’ as more than an aesthetic consideration – it’s a fundamental part of an urban ‘ecosystem’ which improves social interaction and physical and mental health”(4).

MOSS-designed green roof on Dura-Vermeer in Utrecht, including an insect hotel and native plants

SOME GREAT WAYS TO BRING BACK BIODIVERSITY AND A BALANCED ECOSYSTEM TO CITIES:

Bat boxes, insect hotels, native plantings. Look into the history of the land. Was it a wetland? Forest? Prairie? Preserving a piece of this ecological history can not only help balance the native ecosystems, but also make unique city-scapes that create a sense of belonging to its inhabitants.

A great example of this is Qunli National Urban Wetland in China. As a growing city started to take over a wetland, instead of letting the ecosystem die, they created a park around it. Bringing people closer to nature, preserving the native biodiversity, and solving the stormwater management/flooding problem are just a few of the many benefits (5). Nature has the capability to restore itself, all we have to do is give it a push in the right direction.

Photo credits: Qunli National Urban Wetland by Turenscape Landscape Architects (5).

WHY SHOULD WE DO IT?

Along with the Covid crisis, more people than ever are experiencing some form of anxiety and other mental health struggles. Just being in nature 30 minutes a day causes an increase in serotonin. There have also been studies showing the physical health resilience gained by interacting with nature and biodiversity (6).

Just as humans adapt to their environment, plants, animals, and insects do as well. Native plants that have spent centuries in a certain area share ecological history with the environment and require much less if any human intervention. This creates beautiful spaces without the work that most curated monoculture parks require.

Most importantly:

“(Rewilding) would reshape how we feel about public space and who owns it; how we make decisions about our homes; our consumption and eating habits. But it would also evolve our cities into much more dynamic and sustainable engines of survival than the socially-constricting, energy-intensive and life-shortening beasts that they are right now” (7).

Although the climate crisis and fractured ecosystems can seem like overwhelming, unstoppable processes, we all have the capability to change the narrative. Utilizing our global network has the capability to create change in a big way around the world. From bringing nature-centered buildings to our cities to planting native species in your gardens, this movement is about going back to our roots. If this movement compels you, make your voices heard to your local governments and take a step on the wild side (8).

If you want to start rewilding and have a project in mind, reach out to us at info@moss.amsterdam. Our mission is to create wide-reaching and impactful green spaces that are qualitative, inspiring, and conducive to both the wellbeing of people and the harmonious existence with the environment!

SOURCES

- Cockburn, Harry (2020): Rewilding 30 per cent of land ‘would absorb half of CO2 emissions’, The Independent, https://www.independent.co.uk/climate-change/news/rewilding-extinction-climate-change-biodversity-summit-co2-b1050021.html

- Elmqvist, Thomas : Urbanization, Habitat Loss and Biodiversity Decline, Usda, https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/ja/2016/ja_2016_zipperer_001.pdf

- World Health Organization (2018): WHO Global Urban Ambient Air Pollution Database (update 2016), World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/airpollution/data/cities-2016/en/

- Rewilding cities for resilience: Arup, https://www.arup.com/perspectives/rewilding-cities-for-resilience

- Qunli National Urban Wetland: landezine, http://landezine.com/index.php/2014/01/qunli-national-urban-wetland-by-turenscape/

- Trieu, Rosa (2019): Wild Side: 6 Ways Cities Are Turning Urban Settings Into Nature Havens, Redshift EN, https://redshift.autodesk.com/urban-nature/

- Haque, Usman: Making Wild Cities — Notes on Participatory Urban (Re)Wilding, Medium, https://uah.medium.com/

- Azcarate, Juan (2018): Let go of some urban domestication, The Nature of Cities, https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2017/11/13/re-wilding-make-cities-better-just-wilder/